地球上的所有生物共享着同一个物理空间,却用着截然不同的方式丈量它。对于呈现于空间的所有纹理、景观、声音、振动、气息、味道、电场及磁场,每种生物仅仅能够涉足丰满现实的微小部分,被封闭在自身独有的“感官气泡(sensory bubble)”1中,觉察到的仅是广大世界之一隅。

有一个单词可用于概括这种“感官气泡(sensory bubble)”:“Umwelt”,德国动物学家雅各布·冯·奥克塞尔(Jakob von Uexküll)在1909年提出并定义了这一概念,它源自于德语,意为“周遭世界”,奥克塞尔并没有简单将其用来意指动物的生存环境,而是特指动物可以觉察和感知到的周遭世界的部分。2每一物种都受限于某一部分,但又在另一部分中得到解放。例如蜘蛛几乎没有听觉和视觉,它的世界几乎完全由蜘蛛网捕捉到的振动所决定,这是它制作的陷阱也是它感官的延伸。同样,蝙蝠的声纳(回声定位)非常敏锐,能够在黑暗中找到蜘蛛,并精确定位把它从网中揪出。

为了感知世界,动物会探测光、声音或温度等刺激量,并将其转化为电信号,沿着神经元传向大脑。感官将捕捉到的纷乱世界转化为知觉和感受,对此做出反应并采取行动:它们将刺激转化为信息。它们从随机中提取相关信息,从混杂中编织意义,将其他动物与环境联系起来,通过情态、动作、姿势、叫声和电流将彼此相连。

美国哲学家托马斯·纳格尔(Thomas Nagel)在1974年发表的经典文章《成为一只蝙蝠感觉如何(What Is It Like To Be a Bat?)》中提出,动物的意识体验本质上是主观的,且难以描述。以蝙蝠为例,它们通过声纳感知世界,而大多数人类缺乏这种感官。纳格尔写道:“我们没有理由认为它主观上像我们可以体验或想象的任何东西。” 他继续说道:“我想知道的是成为一只蝙蝠是什么感觉。然而,当我尝试想象这一点,我受限于自己的心灵资源,而这些资源对于这项任务来说是不够的。”3思考其他动物时,我们偏袒于自身的感官,尤其是视觉的影响,因为我们的物种和文化极大程度上依赖视觉,甚至盲人也会使用视觉的语言和隐喻来描述世界。人类“Umwelt”的边界往往使我们将其他生物的“Umwelten”(感官世界)隔绝在外。

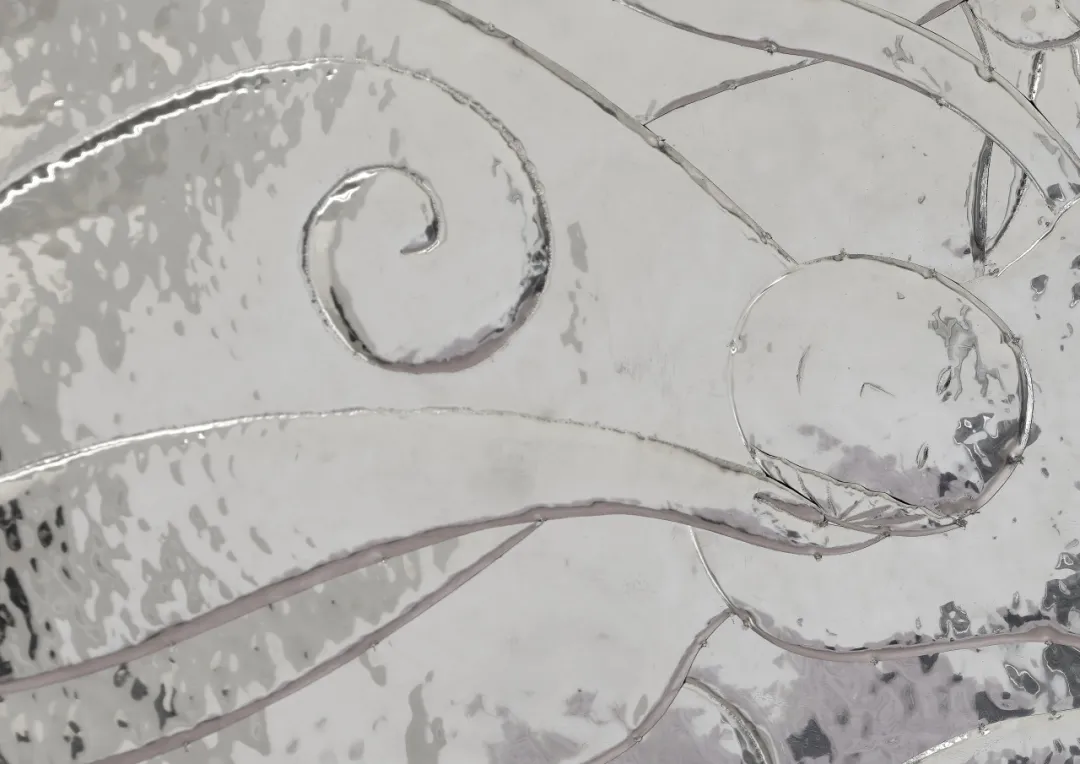

有些生物如鱼、蛇或蜘蛛,它们能够感知到空气和水流中波动的隐蔽信号,而这些信号对我们人类来说是无法察觉的,周围的空气中充满了我们无法识别的线索。蜘蛛的身上布满了数以千计的缝隙感受器(slit sensilla),这些感受器集中在名为“琴形器(lyriform organs)”4的簇状结构中。这些器官的形状像一束平行的线性切口,类似于古希腊用来为诗歌吟唱伴奏的弦乐器:里拉琴(lyre)。通过这些极为敏锐的器官,蜘蛛可以感知到它所站之处任何物体的振动,无论是在地面还是蜘蛛网,这些蜘蛛建构了能够感知振动的界面。对于我来说,这一切都是一个美丽的圆形隐喻,它将艺术的创作和体验与空间联系起来,并深植于诗意之中。

琴形感官5 (虔诚的自由) A Lyriform Organ 5 (Devotion frees),2024

手工锻打不锈钢 hand-hammered stainless steel

210 x 95 x 2.5 cm

琴形感官5 (虔诚的自由) (局部),2024

A Lyriform Organ 5 (Devotion frees) (detail)

琴形感官6 (极度渴望之中)

A Lyriform Organ 6 (In moods of extreme desire),2024

手工锻打不锈钢 hand-hammered stainless steel

45 x 180 x 2.5 cm

琴形感官6 (极度渴望之中)(局部)

A Lyriform Organ 6 (In moods of extreme desire) (detail),2024

All living creatures, while sharing the same physical space, experience it in wildly different ways. For all the textures, sights, sounds, vibrations, smells, tastes, electric and magnetic fields present in the world, every animal can only tap into a small fraction of reality’s fullness. Each is enclosed within its own unique sensory bubble1, perceiving but a tiny sliver of an immense world.

There is a word for this sensory bubble——Umwelt. It was defined and popularized by the German zoologist Jakob von Uexküll in 1909. The term comes from the German word for “environment” but Uexküll didn’t use it simply to refer to an animal’s surroundings. Instead, an Umwelt is specifically the part of those surroundings that an animal can see and experience its perceptual world.2 Each species is constrained in some ways and liberated in others. A spider, for example, can barely hear or see its surroundings. Its world is almost entirely defined by the vibrations coursing through its web a self-made trap that acts as an extension of its senses. A bat’s sonar, on the other hand, is so acute that it could not only find the spider in a complete darkness but pinpoint it with the outmost precision and pluck it from its web.

To sense the world, animals detect stimuli quantities like light, sound or warmth and convert them into electrical signals, which travel along neurons toward the brain. The senses transform the coursing chaos of the world into perceptions and experiences——things to react to and act upon: they turn stimuli into information. They pull relevance from randomness, and weave meaning from miscellany. They connect animals to their surroundings, and they connect animals to each other via expression, displays, gestures, calls and currents.

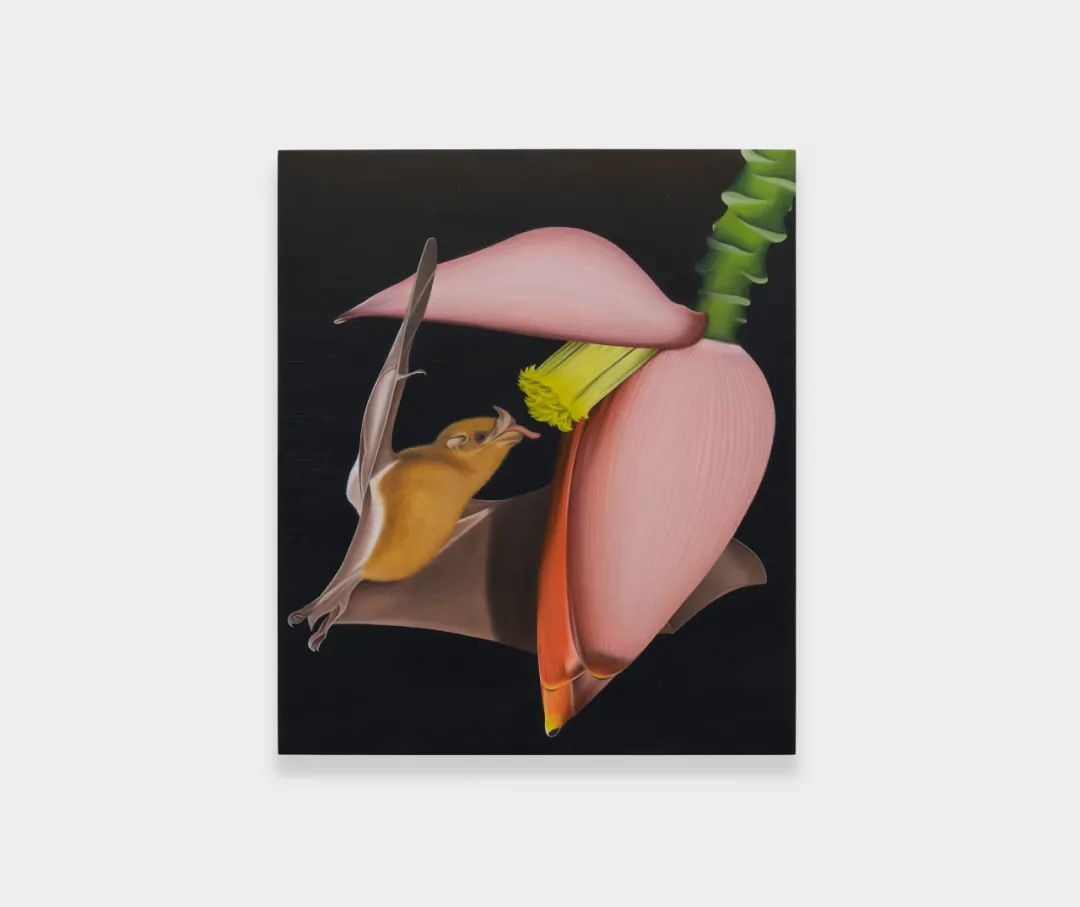

琴形感官(哦,亲爱的……)A Lyriform Organ (O Beloved…),2024

木板油画 Oil on wood,35 x 30 x 3 cm

In his classic 1974 essay “What Is It Like To Be a Bat?,” the American philosopher Thomas Nagel argued that other animals have conscious experiences that are inherently subjective and hard to describe. Bats for example, perceive the world through sonar, and since is a sense that the majority of humans lack, “there is no reason to suppose that it is subjectively like anything we can experience or imagine,” Nagel wrote. “I want to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat. Yet if I try to imagine this, I am restricted to the resources of my own mind, and those resources are inadequate to the task.”3 In thinking about other animals, we are biased by our own senses and by vision in particular, given that our species and our culture are so driven by sight that even blind people will describe the world using visual words and metaphors. The boundaries of the human Umwelt often make the Umwelten of others opaque to us.

Some creatures like fish, snakes or spiders can feel the hidden signals that flow, blow and ripple through air and water, but such signals are undetectable for us humans. The air around us is full of cues that we don’t identify. A spider’s body is covered in thousand of slit sensilla: vibration sensing cracks gathered into clusters called lyriform organs.4 Shaped as a bundle of parallel linear incisions, it resembles and is suitably named after a lyre: that stringed musical instrument used to accompany poetry recitals in Ancient Greece. Using these exquisitely sensitive organs, spiders can sense the vibrations coursing through whatever they’re standing upon, either the ground or its web. These spiders construct the surfaces that they then sense vibrations through. I find all this a beautiful round metaphor of making and experiencing art in relation to space and grounded in poetics.

1. 概念引申并翻译自普利策奖得主、科学记者埃德·勇(Ed Yong)2022年发表于《大西洋月刊(The Atlantic)》的文章“How Animals Perceive the World(动物如何感知世界)”。感官气泡描述了不同生物在共享相同的物理空间时,所拥有的个体化的知觉世界,就像气泡一样圈定了各自的感知范围。

2. How Animals Perceive the World, Ed Yong, The Atlantic, July/August 2022 Issue

3. What Is It Like to Be a Bat?, Thomas Nagel, The Philosophical Review, Vol. 83, No. 4 (Oct., 1974), pp. 435-450, Duke University Press on behalf of Philosophical Review Stable

4. “lyriform organs(琴形器)”一词最早是由高伯特(P.Gaubert)(1890年)用来描述在蛛形纲动物腿部和其他部位发现的一组奇特的感觉器官。

Words by Rodrigo Hernández

文字为艺术家对展览标题所作解释

图文致谢艺术家及天线空间

罗德里戈•赫尔南德斯(墨西哥,1983)生活和工作于里斯本和墨西哥城。曾就读于卡尔斯鲁厄美术学院和马斯垂克的扬·凡·艾克学院。他曾是巴塞尔Laurenz-Haus基金会(2015)、斯图加特孤独城堡基金会、巴黎国际艺术城(2016)和伊斯坦布尔现代美术馆(2019)的研究员。

罗德里戈•赫尔南德斯主要使用传统的艺术创作媒介和技法,包括素描、雕塑和绘画。他主要的兴趣是探讨艺术图像中的构成与其流变,且从中美洲的图像学一直跨越到当代艺术实践。他的项目形式多样,从工作室中的物件制作到特定场域的创作实践,或是研究型导向的项目构建皆有涉及。他从多种美学参考中汲取灵感,这些参考范围从日本古典版画及时尚艺术、欧洲现代主义等,以此发展出极具个人特色的形式语言。

他最近的个展包括:“with what eyes?”,加州艺术学院沃迪斯当代艺术中心,旧金山,美国(2024);“Flux of Things”,凯斯特纳协会展览馆,汉诺威,德国(2023);“El Espejo”,Museo Jumex,墨西哥城,墨西哥(2022);“I Am a Stranger and I Am Moving”,瑞士学院,纽约,美国(2022);“El Espejo”,Museo de Arte Moderno,麦德林,美国(2022);“Petit Musc”,Kunsthalle Kohta,赫尔辛基,芬兰(2021);“Pasado”,CIAJG,基马拉斯,葡萄牙(2021);“Dampcloot”,Galerie Fons Welters,阿姆斯特丹,荷兰(2020);“A Moth to a Flame”,萨凡纳艺术与设计学院美术馆(SCAD Museum of Art),萨凡纳,美国(2020);“What do I hear when I hear the flow of time?”,西凯洛斯艺术博物馆,墨西哥城,墨西哥(2019);“O mundo real não alça voo”,Pîvo,圣保罗,巴西(2018);“Who Loves You”,温特图尔艺术中心,瑞士(2018);“A Complete Unknown”,Midway Contemporary,明尼阿波利斯,美国(2018);“THE GOURD & THE FISH”,SALTS,瑞士(2018);“The Shakiest of Things”,Kim? Contemporary Art Centre,里加,拉脱维亚(2017);“I am nothing”,海德堡艺术协会,德国(2016);“Every forest madly in love with the moon has a highway crossing it from one side to the other”,Kurimanzutto,墨西哥(2016);“El Pequeño Centro”,乔波大学博物馆,墨西哥(2016);“Go, Gentle Scorpio”,Parallel Oaxaca,墨西哥(2016);“What is the Moon? ”,博尼范登美术馆,荷兰(2014)。

他的作品曾在以下机构展出:海牙美术馆;明斯特艺术宫;哥德堡艺术中心;伊斯坦布尔现代艺术博物馆;平丘克艺术中心;贝加莫现当代艺术馆;卡尔斯鲁厄媒体艺术中心;纽伦堡艺术中心;博尼范登博物馆;格莱斯顿画廊;墨西哥城现代艺术博物馆;莫斯科现代艺术博物馆;苏黎世装置艺术之家;巴塞尔美术馆。

Rodrigo Hernández (Mexico City, Mexico, 1983) currently lives and works between Lisbon and Mexico City. Studied at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Karlsruhe, and at Jan Van Eyck Academie in Maastricht. He has been a fellow of the Laurenz-Haus Stiftung in Basel (2015), Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart, Cité International des Arts in Paris (2016) and Istanbul Modern (2019).

Working mostly with classical medias and techniques of art making, including drawing, sculpture and painting, Rodrigo Hernández is interested in the constitutive movement of art and image making, from Mesoamerican iconography to contemporary art. His projects vary from object making within a devoted studio practice to site specific and research oriented projects. He draws on a number of aesthetic references, which range classical Japanese printmaking to fashion, and European modernism, among others, to develop a very personal formal vocabulary.

His recent solo exhibitions include: with what eyes?, CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco, US(2024); Flux of Things, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover, DE(2023); El Espejo, Museo Jumex, Mexico City, MX(2022); I Am a Stranger and I Am Moving, Swiss Institute/Offsite, New York, US(2022); EL ESPEJO, Museo de Arte Moderno, Medellin, CO(2022); Petit-Musc, Kunsthalle Kohta, Helsinki, FI(2021); Pasado, CIAJG, Guimaraes, PT(2021); Dampcloot, Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam, NL(2020); A Moth to a Flame, SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, US(2020); What do I hear when I hear the flow of time?, Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, Mexico City, MX(2019); O mundo real não alça voo, Pîvo, São Paulo, BR(2018); Who Loves You, Kunsthalle Winterthur, CH(2018); A Complete Unknown, Midway Contemporary, Minneapolis, US(2018); THE GOURD & THE FISH, SALTS, Birsfelden , CH(2018); The Shakiest of Things, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, LV(2017); I am nothing, Heidelberger Kunstverein, Heidelberg, DE(2016); Every forest madly in love with the moon has a highway crossing it from one side to the other, Kurimanzutto, Mexico City, MX(2016); El Pequeño Centro, Museo Universitario del Chopo, Mexico City, MX(2016); Go, Gentle Scorpio, Parallel Oaxaca, Oaxaca, MX(2016); What is the Moon?, Bonnefanten museum, Maastricht, NL(2014).

His work has been exhibited in venues such as: Kunstmuseum Den Haag; Kunsthalle Münster; Göteborg Konsthall; Istanbul Modern; PinchukArtCenter, Kiev; GaMec, Bergamo; ZKM Museum für Neue Kunst, Karlsruhe; Kunstverein Nürnberg; Bonnefanten museum, Maastricht; Gladstone Gallery, Brussels; Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City; Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Moscow; Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zürich; Kunsthalle Basel, Basel.